Class of 2022: Student’s medical school flight plan takes her in new directions

Lynn Stanwyck came to the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine (VTCSOM) with a strong grounding in physics and astronomy. As her medical career began to lift off, the fourth-year student remained committed to her passions and has soared to new heights with clerkships in aeronautical medicine at NASA and with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

“Physics is very intellectually stimulating, and I love that, but I chose medical school because I wanted to see my direct impact on people,” she said.

Stanwyck is one of three medical students who will receive their graduation hoods and diplomas in a ceremony at 9 a.m. Dec. 17 at the school’s Roanoke campus.

As an undergraduate physics major assisting with weighty research on topics such as astrophysics, soft condensed matter, and biophysics, Stanwyck was certain opportunities existed to bring physics into her medical studies. She was right.

In June 2021, she took a six-month leave from medical school to intern with the FAA’s Office of Aerospace Medicine. She worked with other interns and flight surgeons, scouring medical databases to recommend updates to medical policies for pilots. During this time, Stanwyck immersed herself in data regarding conditions such as aortic aneurysms, macular degeneration, and diabetes. The FAA will use the findings as reference materials for future policy updates.

Stanwyck’s policy work on diabetes guided her in another direction during her internship when she led a team that took a deep dive into the stringent FAA policies regarding pilots with insulin-treated diabetes mellitus (ITDM). In 2019, the FAA began granting certification to first- and second-class pilots with ITDM who were part of a continuous glucose monitoring program. This meant if a pilot had a mostly steady blood sugar level over time, for example, the FAA could issue flying certification with confidence.

“We went back and looked at pilot data noting key variables and were evaluating the ITDM protocol to see if it was doing as well as we thought,” Stanwyck said.

Her study found that out of 200 pilots identified with ITDM, 55 were granted certification and 22 were denied.

“We determined the FAA program has successfully medically certified pilots with ITDM. Also, these pilots were shown to have better diabetes control and had less potential for hypoglycemia,” Stanwyck said. She presented these findings at the Aerospace Medical Association annual meeting.

“This internship was great because I was involved for a long stretch of time and I had a medical background. Both of these made me feel like I could really contribute,” she said.

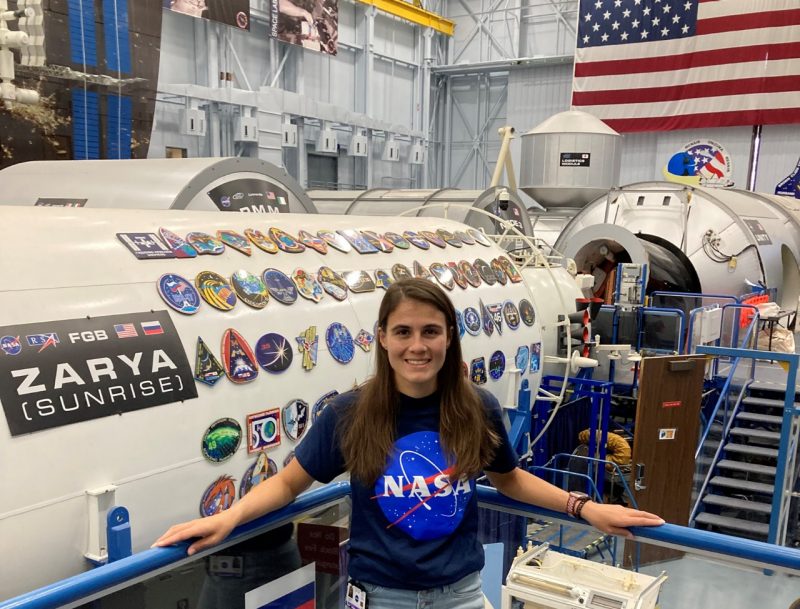

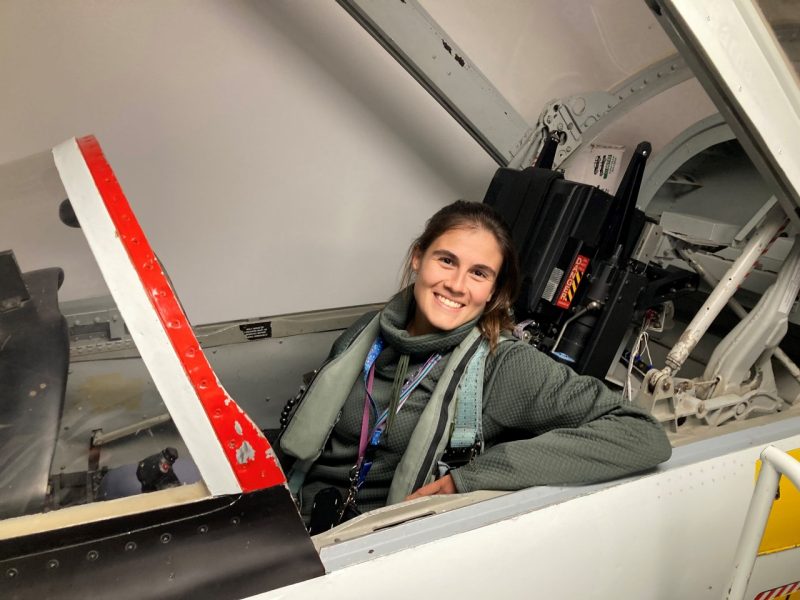

In October, Stanwyck set her sights even higher, so to speak, and found her way to Houston for a medical clerkship at NASA.

For the month-long project, she worked with NASA’s precision health team conducting an exhaustive literature review looking at a gene called ACTN3, which is associated with high-performance athletes. Essentially, people who have a common ACTN3 mutation are potentially more suited to endurance sports, while the nonmutated form is associated more with sprint and power performance. In addition, the mutation has some limited evidence of higher risk for certain types of injuries.

“Knowing whether or not an astronaut had the ACTN3 mutation could help personalize their training regimens before going into space and while they were in space,” Stanwyck said. “NASA’s not going to be doing genetic testing any time soon, and it will not be used as a selection criterion, but there’s a potential to use it for something like optimization of training.”

While the precision health project was an important part of her clerkship, there was also time for lectures and tours of some really “cool” stuff.

Take, for instance, the neutral buoyancy lab, a large indoor pool that is approximately 40 feet deep and holds over 6 million gallons of water. It houses mock-ups of part of the International Space Station and allows astronauts to perform simulated extravehicular activities in simulated microgravity in preparation for upcoming missions. Trainees wear spacesuits to get used to moving in the suits, making sure that they fit properly and to troubleshoot the types of movements they will be doing on their actual space walks.

“We were allowed on the deck of the pool, but that’s as far as we could go. There were divers all around making sure everything’s OK and a physician who supervises the astronauts for possible decompression problems or muscular skeletal issues from the strain of spending multiple hours in bulky spacesuits,” she said.

In terms of opportunities to continue on with aerospace medicine after medical school, Stanwyck said the sky’s the limit. Stanwyck can continue with aerospace research or consulting. In addition, the University of Texas Medical Branch offers an aerospace medicine residency, which opens doors at NASA.

“But I would be happy also just practicing medicine and doing research on the side. There are so many opportunities out there,” she said.

Rebecca King and Rocco DiSanto also will graduate on Dec. 17. Originally scheduled to graduate in May, they each took extra time during medical school. DiSanto spent an extra semester working with the Virginia Department of Health in support of its COVID-19 response and pursuing additional research. King took the spring semester as maternity leave after giving birth to a son in November 2021.

“Our curriculum is geared for four academic years,” said Aubrey Knight, senior dean for student affairs. “Students who take time off to pursue master’s degrees, clerkships, or research fellowships usually take a full year, which would have them graduating in May the year following when they normally would. It’s unusual for us to have three December graduates, but each of these outstanding students has made us proud in their achievements and pursuit of what matters most for them.”