Doing What Needs to Be Done

Mallory Blackwood

The VTC Narrative Medicine class has a beautiful way of forcing its students into delightful situations which couldn’t be organically fabricated without the pretense of an assignment. “I have to do an interview for school” gives one license to dig through a person’s history, hopes and fears. So, when we got our assignment to interview someone we knew well, but whose health history we knew little about, I jumped at the opportunity to talk with my Uncle Kerry. In a family as large as ours, it is easy to see a person often without learning much about their early life. Although Kerry and I have always had great discussions about politics and burgeoning science, I knew almost nothing about his health prior to this interview. This narrative and the accompanying sculpture are reflections of the two-hour conversation spent rectifying that deficit.

Kerry has spent the 61 years of his life surrounded by medical professionals. He has been married to a nurse for four decades, both his parents were doctors who immigrated here from Ireland, and his daughter is now a doctor in the U.S. As we speak, I’m aware that because of this, he likely has more medical knowledge than I do only a few months into my medical education. I try consciously to shift out of niece mode and into the role of a clinician.

Kerry often tested positive on TB tests as a child. This was not, he says, due to a history of TB, but due to its prevalence in Ireland at the time and his proximity to his parents who had both contracted the disease. Despite his exposure to medicine through both his parents, Kerry cites his first interaction with the hospital system as an episode of Rhabdomyolysis in college. He was hospitalized for a week before a diagnosis was made, circling the rim of complete kidney failure during this time. The inciting event was a set of several hundred pushups he did as part of a hazing ritual for a fraternity he was pledging along with some teammates (Kerry played Division I soccer in college). At the time, Kerry describes being unconcerned with his presentation and hospital stay and eventual transfer to a larger hospital. He says he benefited from ignorance about the severity of his condition, something he claims to benefit from again later in life when his first two children were born with life-threatening complications.

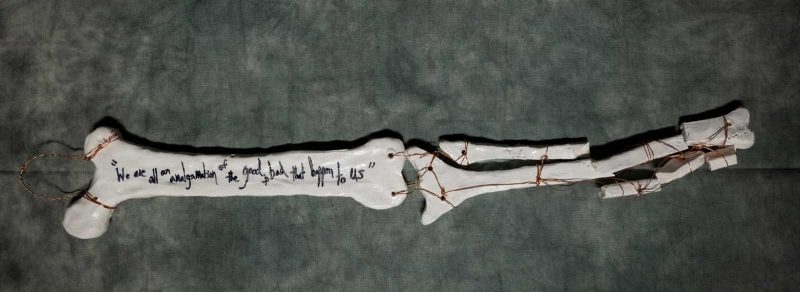

Kerry’s active lifestyle in college would be the cause of another important health event the year following his brush with Rhabdo. After three seasons on the soccer team, he shattered his fibula and tibia against a tree while skiing. Kerry states that the recovery was long, painful, and inconvenient. He underwent extensive surgery and spent two years in a cast. He was no longer able to play soccer and to this day feels uneasy skiing since the boot hits his calf right at the break site. Despite how traumatic this ordeal sounds, Kerry remained upbeat. He described “doing what needed to be done.” He designed a sling so that he could bathe himself and requested a special removable cast be made so that he could swim for exercise (there were no waterproof casts at the time). Here, and at other moments of our interview, Kerry inadvertently describes an impressive amount of self-advocacy. When I brought this observation to his attention, he was surprised--as though it hadn’t occurred to him that not everyone would come up with such a creative solution.

Now, years after all the surgery and rehab, he faces the new challenge of arthritic hip and knee pain. One leg is shorter than the other since his accident, and his bones are beginning to crumble under the added strain of an uneven gait.

I probed about the impact this had on his social life, since his closest friends were all soccer players. To my surprise, he described these friends being committed and supportive people despite his being permanently benched. In addition to this support system, Kerry had his parents whom he moved in with over the summer. They were, fortunately, more than qualified to take care of him. At home, a new sickness was identified. In a time before the addictive potential of opiates was widely known, Kerry had become dependent. His parents noted that the mental fog and headaches he complained of in the morning might be related to the medication. Remarkably, he kicked the habit over that summer at home and has refused opiates ever since.

Difficult though this time in his life sounds, I did notice a silver lining: Kerry originally attended college for a business degree. His passion was science, but with away games for soccer, he couldn’t attend labs. Ironically, being benched from the field gave him a spot at the lab bench. He took on a second major and graduated with two degrees: one in business and one in geoscience. This is the Kerry I know: a scientist’s mind with the practicality of a business owner. None of this would have happened if he hadn’t caught an edge while skiing his sophomore year of college. I asked what he might have done if he hadn’t gotten into science. He doesn’t deal much in hypotheticals, but he supposed that he would be much less happy.

This incident also pushed back his graduation date--something that allowed him to meet his future wife. He wouldn’t have become the person he is today without this setback. Kerry was surprised to hear me point out these “silver linings.” He responded, “Well, I suppose we are all an amalgamation of the good and bad things that happen to us. Hopefully,” he continued, “for you it is more good than bad.” Luckily, it has been. In this moment, I stumble back into my role as his niece. I want him to know that I am well, and happy, and appreciative of the groundwork this family has laid for me and my cousins.

I asked Kerry throughout our interview how these sicknesses affected his outlook on life. To my surprise, they didn’t make him more hesitant towards the active lifestyle he had always led. I know him now to be an avid cyclist, but I didn’t know that he does this because of his leg, which still bothers him if he runs. Still, he says being active is the most important factor in his quality of life. He wants more than anything to hang onto his ability to move, and to stay independent. Pain, he says, he can handle. Cancer he treats as a certainty between his family history and the basal cells, melanomas and colon tumors he has had throughout the years. He is vigilant in his surveillance of these malignancies, but doesn’t seem to fear them. What he really fears is losing his freedom of movement and improvisation--his ability to keep “doing what needs to be done.”

Mallory Blackwood

Class of 2022