David Hartman - Video Transcript

This recording was part of an event hosted by the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine titled "disAbilities at Work: Thriving in an Abled World" held on October 11, 2022. Use the links below to visit the event page, or the recordings and transcripts of the other two speakers, Dr. David Hartman and Carrie Knopf.

Links to demonstrated assistive technologies for the blind

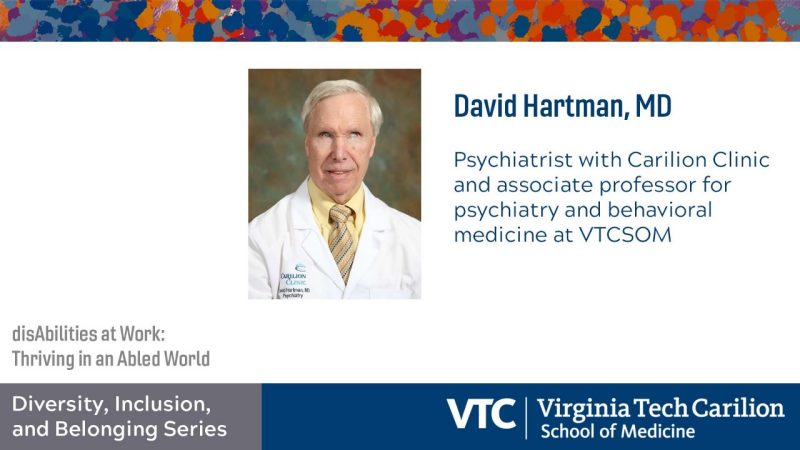

[0:00] >> [Vianne]: Our next speaker this evening is Dr. David Hartman. Dr. Hartman is a psychiatrist with Carilion Clinic and Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. He will share history of how as a blind person he lives and thrives both personally and professionally. Dr. Hartman is consistently named by his peers to be among the top three psychiatrists in the Roanoke Valley. His work in the treatments of opioid addiction is well-known. In 2019, he received the National Addiction Champion Award from the National Conference on Addiction Disorders, NCAD. Closer to home, he has been instrumental in establishing Carilion Clinic’s office-based opioid treatment clinics. David Hartman's philosophy is that everyone has a disability. Those who are most disabled don't know what their disabilities are and those who are least disabled are those who can turn their disability into advantages. Imagine what you CAN do. Thank you, Dr. Hartman.

>> We have sound?

>> We have sound and we're back online. Thank you sir for your patience. [LAUGHTER]

David Hartman, MD

[1:13]>> [Dr. Hartman]: Welcome. And I wanted to just start out by really praising Mark for his presentation and it really gives me new vision of opportunities ahead of me and I thank you. And my plus one is we need to figure out how to get the electronic medical record EPIC figured out to be more accessible. So that's a project maybe we can talk about.

[1:39] Vianne Greek has been my angel. She has helped me through various technical logical struggles and she is really one of the most patient people I've ever met and she's also the one I want to thank for, I think arranging for this talk.Dr. Kemi Bankole and Dean Learman, I appreciate your support of this lecture as well. My wife who helped me get all my toys here and I wanted to thank her for all her support Cheri’s over in the room here.

The cab driver and the monkey

[2:14] I came to Roanoke in 1982 after being on the faculty and realizing I wanted to see more variety in psychiatric patients. So I came here, joined a private practice, George Lukey, who didn't blink an eye of the idea of a blind doctor joining him. He accepted me as I was. As I joined his practice, a small private practice, I had to travel from south Roanoke to LewisGale where I was practicing and I took a cab every day. And people said why it's very expensive, how did you afford it? Well, if you think about it, my wife and I are two different professionals. We would have had two different cars. It's a lot cheaper than a second car to take cabs. And so I would get up in the morning and run out and get a cab to LewisGale Psychiatric Center.

[3:19] There's one morning I got up and I was sitting down on the couch next to various toys my three-year-old had and my newborn had, and I got my briefcase. I don't carry that anymore, but in those days, this was a number of years ago, I had a briefcase and I got everything together and packed it up, shut it, and ran out and got the cab. And as I got in the cab, I started feeling around in the back of the cab and it was amazing to me, this cab driver had a stuffed monkey in the back of his cab and it looked just like my son's stuffed monkey and I started feeling it, picked it up. I realized that the paw was caught in my briefcase. So I realized that when I shut my briefcase on the couch, I'd caught my son's stuffed monkeys paw. Now, I just want us to imagine a cab driver driving up to our house and sitting there watching a blind man with a briefcase running out the door with a monkey clinging to it, jumping into the backseat and says, "Take me to the LewisGale Psychiatric Center." I don't think he stopped for a red light.

The biggest obstacle is society's low expectations

[4:50]>> So I think it was about eighth or ninth grade when I began thinking of this crazy idea to go to medical school. I'd lost my sight at eight years of age, and so I was without sight and when I started expressing this idea of wanting to go to medical school, to my shock, the obstacle was not what I could or could not do as a blind person, it was society's low expectations of what I, as a blind person, could do.

[5:27] I went to a school for the blind, Overbrook School for the Blind, in Philadelphia. While I was there, about the age of 9, 10, and 11, I was required to spend two years learning to be certified as a basketry weaver. Well, I was a little frustrated because I saw so many other things I should be learning. And I went to our assistant principal and I said, "There should be something else I should be learning other than basketry." And he looked at me and he says, "You know, Dave, you need a backup. If your chosen career falls through, you need to be able to have a backup career."

[6:05] It gives me so much confidence if all my patients leave me, I'm not able to find a place to work, I can weave baskets now. Well, sadly even a school for the blind had such low expectations of what I as a blind person could do.

[6:26] Well, there are many myths about blindness, I think we've heard of some of the one that is my favorite, is that if you talking to someone that's blind, you have to talk loud to them. Of course, that's ironic, often we're a little more aware of what we hear.

Assistive technology in college

[6:49] So I went through high school and had this crazy dream, and went to a small college in Pennsylvania, called Gettysburg. And I was able to persuade my professors there to support my crazy idea of being a biology major and a pre-med student. We were able to use a raised line drawing kit. Admittedly this was 50 years ago and we had this cellophane over a rubber pad. And if you drew a line on it, it formed a raised line. I was able to learn histology by the professor's drawing the various structures, or giving me models so that I could feel them. I was able to learn comparative anatomy by feel. I had a student sit down with me every day and help me learn the various structures. He got the highest grade in the class, and I think it enabled him to learn a little better, to be able to transfer it and teach me.

Beheading cockroaches

[7:57] I would sit next to a student in physiology class learning the lab, the student that I was with would describe what he was doing, let me know the experiments, and I appreciated the process. But I began to feel like out of touch, I wanted to be involved in the experiment. So I went to the professor and he said, "Well our next lab is going to be interesting. I think you can help us be more involved in that lab."

[8:27] Well, the next lab happened to be studying - I know you're all going to be fascinated with this - the digestive tract of cockroaches. And so he came to me and he says, "Dave, here's what we're going to do. You grab the cockroach, got to grab them quickly because they wake up and they start moving around." He says you pick any up here and you pull the head off in this way. And if you do it right you'll get the whole digestive tract with it. I must admit I felt very involved in that study.

Recordings for the blind (Learning Ally)

[9:04] So there were a lot of books I needed, and there's an organization in New York City, called Recordings for the Blind. Now it's called Learning Ally. And if you sent them two copies of a textbook, they would record it and send me a recorded tape. Initially, it was the reel to reel tape. And I must admit it was a little challenging because I wished professors would say, "We'll just start with first reel and go to the last reel," but they never did that. They'd always say, you begin on Page 452, and read to 695. And going through a reel-to-reel tape and finding, that was always exciting. But it was a great opportunity, and Recordings for the Blind, now Learning Ally, did so much to enable me to get through medical school.

Medical student at Temple University

[10:02] As I said, I did finish four years of college at Gettysburg. And to my amazement and delight, I was accepted to a medical school, Temple University School of Medicine. And I'm very grateful for their willingness to do two things. One is their willing to take a risk, to take a chance to see what I COULD do. So often people are a little hesitant for that risk. Temple was not, they're willing to step forward to take that risk. They were also willing to assess not only what I could not do, but what I COULD do. I think too often, and I know in the medical field we do this, we see what the problem is, what the element is, the disability, and we forget to look at, how can this individual compensate for their impairment?

[10:57] Well during the first two years of medical school, in those days it was very much basic science. I know now we're doing more clinical work in the first two years. But in those days it was basic science. I was able to implement the various strategies I used in college.

Blindness was minor impairment during medical school

[11:17] The second two years I was shocked and amazed to realize how little impairment blindness was. About 85% of a diagnosis is based upon a good history. And I think that being able to listen to my patients, ask the right questions, was the more important area. And you didn't need sight to do that.

[11:42] Now obviously doing a physical was very important. And to my amazement, I realized that most of the physical is based upon touch, and listening, and even smell. Whereas only a few parts of the physical, looking in the eyes and ears, is totally dependent on sight. And these areas I was able to have colleagues describe to me what they were seeing.

Choosing psychiatry

[12:12] Well at the end of medical school I chose to go into psychiatry. I actually did a year of rehab medicine and then went into psychiatry. And I chose Psychiatry 1 because I love to hear people's story. I think it's so important to hear individuals' experiences, what they went through. But also I love psychiatry because it deals with quality of life, not just quantity of life. Medicine focuses on how long we can keep people alive, but what psychiatry does is make that extra life valuable and worth living. [59:30] So I went into psychiatry, and I'm going to share some experiences that I've had over these 40 years. When I first began seeing patients, one of my worries was when I was on a locked unit I didn't want to inadvertently leave a patient off the unit, where they would possibly become actively suicidal or hurt themselves. I wanted to make sure that when I went on the unit that I made sure no one snuck out or walked out on me. So I went on the unit, and this was in the '80s. The rehab unit here, fifth floors, was the locked unit. And I would walk up to the door, put my foot behind the door, and then gradually pull the door open and slither in. I called it the slither method. And I got very good at it, but no one ever tried to escape, until one night.

An escapee from the locked psychiatry unit

[13:57] It was about 8:30, and I put my foot behind the door, I unlocked the door, gradually opened it, and suddenly someone burst out. Well, I was ready, I'd had worked it out in my mind exactly what I wanted to do. And I grabbed the person. It was a woman about five foot, very stocky, and I grabbed her across the chest. It was a little awkward, but I didn't want to let go because she would escape. And I said, "Ma'am, who are you?" And she didn't say anything, and said, "Ma'am, who are you?" And finally, she goes, "I'm a visitor." I said we do free physicals and so it was good.

The angriest patient I've ever encountered

[14:48] I often experience these awkward situations, and we use humor, we laugh about them, we expect them, and we move on. And that's what we did in that situation. I remember another situation where I was seeing an outpatient, and I walked into the waiting room and greeted the person, and then said, "Just follow me back." And I walked back to my office, shut the door, sat down, and said, "How are you doing?" Silence.

I said, “Well, how was your week been?” Silence. Well, I knew this person was probably seething with rage. And I said, “Well, ma'am, I think we need to talk about it”. Silence. And then there was a knock on the door. And I thought, how could someone be interrupting me in the midst of this very intense session? Well, got up, went to the door, and there was my patient. She had walked into the wrong room. She was waiting for me and I was waiting for her. [LAUGHTER] So again, awkward situations come up and we work our way through it.

Patient experience with lack of eye contact

[16:17] I went to the emergency room and saw various patients there. This one day I went and a lady had been evaluated and noted to be very paranoid. And when I start to interview her, she explained that the devil was chasing her. And I said, well, who is this devil? She said, it's you. Well, I know my wife has suspected that on occasion, but I reassured her I was not the devil. I said, Why do you think I'm the devil? And she said, well, your eyes, they're very strange. And what I realized was the lack of eye contact made her feel a little offset. She didn't know how to put that together, that my eyes were drifting around the room. And so I simply explained to her that I was blind and that I would not be able to give eye contact and that we would proceed and I assured her that I wouldn't harm her. And she felt much more relaxed. It made sense to her and we were able to finish the visit. But [COUGH] since has made me very aware of sometimes the lack of eye contact puts people off and it's something people have to adjust to.

General patient experience with having a blind doctor

[17:50] Well [COUGH], on a general note, I've been very fortunate patients have accepted the fact I can't see. I think in some cases they are relieved that I'm not sitting there peering at them, or staring at them. I remember one Saturday I came in to see a patient after she was newly admitted and did an interview and she was very nice. She said, Dr. Hartman, I really appreciate your efforts. I know that you're very sincere and very competent, but I've got to be honest with you. I feel uncomfortable with a blind doctor. And she said, would it be alright for me to have a sighted doctor. Well, I had a partner, Dr. Lukey, who had brought me down here and have been very supportive. And I said, sure, Dr. Lukey will see you on Monday and I will be glad to see you today and tomorrow, but I will make sure that you have a sighted doctor on Monday and I think you'll feel more comfortable. Well, I saw her on Sunday. And then I went in Monday and I started talking to her and I said, now, Dr. Lukey is here, he'd be glad to see you, he's sighted. She said, well, wait a minute, I've gotten used to you and I've adjusted to the fact you can't see, and I'd really rather just stay seeing you. And I think that's probably not uncommon that people have that initial reaction not knowing how to interact with someone that's totally blind.

The journey to Carilion

[19:25] Well, as I said in 1982, I joined Dr. Lukey, who was incredibly open and accepting of the fact I couldn't see. He brought me to Roanoke and introduced me to the community and was a great support and we maintain a wonderful friendship. He has since retired.

[19:46] And then in 2005, I had been working at LewisGale Clinic and they went through some business changes. And I was looking for new opportunities and I had this magical call from Dan Harrington. Dan was chairman of our psychiatry department here at Carilion. And he had the courage and the willingness to just call me up and say, Dave, we'd like you to join our faculty and our program here at Carilion. And I think it took a lot of courage just to step out and say, We don't care if you're blind, sighted, deaf whatever. We would like you to join us. And I owe a lot to Dan Harrington for being able to just step up and invite me to join the faculty and the program here at Carilion.

[20:44] I've had a wonderful 17 years here at Carilion appreciated their support. I feel very blessed. And over the last few years I've worked with my wife and dealing with addiction, opioid use disorder, and that's been a real privilege.

Assistive technology in the workplace

[21:05] I'd like to take a few minutes and just introduce you to some of my toys that I have used. The equipment that have enabled me to accomplish some of the challenges.

Canute E-Reader by AmericanThermo

This machine that you see in front of me is a braille display. It's really amazing. It has nine lines and each of these lines have these movable dots that move up and down. And you probably heard me push a button and the noise when those little beads move up and down forming the braille spaces.

How assistive technology has changed over the years

[21:43] I also want to talk a little bit about how technology has changed over the years. When I lost my sight in 1958, I used these records that had books that were recorded on them and they were read by various volunteer readers. They were wonderful. I could lie on my bed and listened to a book like Les Miserables and it was just a great way to read. Unfortunately, I'd order a book, it would take three months for it to be sent to me. And it was a little frustrating waiting for it, but it was magical when I got it. Over the years, I got connected with Recordings for the Blind , as I mentioned earlier, where they would record books specifically for me.

[22:43] But today, I'm able to go on the Internet and go to the same library. And I can digitally download a book. And within 20 minutes, I could have gotten Les Miserables and started listening to the book.

The human element of assistive technology

[23:03] In the 1980s, I depended a great deal on nurses. They would read charts to me. They would follow various prescription orders that I would give. I'd call pharmacists and they would fill prescriptions. So I did a lot of it by working with various people.

[23:27] I would get articles and have my staff read the articles for me so I can keep up to date with various developments.

The invention of the electronic medical record

In the 1990s, there was the development of the electronic medical record, and in the '90s, it was fairly primitive. And so the adaptive technology I had the braille displays that I have were able to use the electronic medical record and change it into braille and voice so I could use it quite easily.

[24:09] When I joined Carilion though they had invested in Epic, which is electronic medical record out of Verona, Wisconsin. And the complexity of that program has made it very difficult to adapt to. But I'm going to show you in a minute what I've been able to accomplish.

[24:29] In the '90s I was able to get my first computer and computers transferred print into voice, which was like a miracle for me. And I was able to develop recorded material that I could listen to. It was really a major step forward, allowing me to be much more independent. I'm going to just show two different pieces of equipment. The first one is a note-taker.

[25:15] Now the display I've been using for notes is a wonderful tool for reading pages of notes. I can read a whole page at a time. The problem is, I can't change those pages. I can't write on this device and it doesn't go on the Internet.

Freedom Scientific's EI Braille

[25:56] This other equipment is basically a Braille laptop. It has no visual input, but it has auditory and braille display. So this note-taker, as I said, is like a braille laptop, and it has one line of braille. It has a button that pushes me up and down so I can look at the first line, the second line, the third line. I can't see all those lines at once. It also goes on the Internet. And like most computers, it takes a minute or so to wake up. So it'll wake up in a minute. And then you'll also hear its speech, and is just about there. And this note-taker allows me to read emails. It allows me to go on the Internet. It allows me to write notes, allows me to go to websites. I could download a Braille book. I could download a recorded book onto this machine. And I think it's just about where it needs to be. There it is. It uses Windows, so it's the same there.

[27:14]>> One of 13.

[Dr. Hartman]>> So it has a mechanical voice

[COMPUTER GENERATED VOICE]: >> Recycle bin. 3 of Braille Quickstart Guide 4 of 13. Taskbar.

>> [Dr. Hartman]: And Vianne Greek and I struggled to download some programs on it. That was a challenge, I’m sure Vianne struggled with my limited technological skills.

>> [OVERLAPPING] [Computer]: browser to move through items press email, M. [OVERLAPPING]

>> [Dr. Hartman]: So that would bring the email. So it gives me an opportunity to read email, take notes.

>> [Computer]: [inaudible] select the list box, not selected, two unread Medscape, CME and education. Are you effectively managing patients with schizophrenia. Two messages in conversation for 10:00 am Medscape Education [inaudible]. [OVERLAPPING].

iPad with Voiceover and a Braille Bluetooth Keyboard

[28:01] >> [Dr. Hartman]: I'm going to shut it off, but that gives you a feel for that little device. Now, the challenge has been to work with the electronic medical record. And Mark, I may be tapping you for ways to do it, but what I've been able to devise is, I know that there is a form of EPIC called Cantos that you can put on your iPhone, I mean iPad. So I have an iPad here. I'm going to turn it on. And then I have a braille display that has a Bluetooth that connects to that iPad. And the Braille display, again, is one line. And I've just got the two connected. And you can hear where this braille display, it not only moves down the iPad screen, but it reads and then the iPad has Voiceover, which I don't know whether you're aware of this, but all iPhones have Voiceover. You can go to it and they'll read what's on the screen. So it allows me to read what's on the screen. Well, that's just a simple numbers that it's reading. And then if I want to activate them, I just push a button which activates them.

[Note to the audience. Vianne chose not to hold the microphone to the Braille device while the iPad on the home screen so that we would not reveal Dr. Hartman’s iPad passcode.]

[COMPUTER GENERATED VOICE] >> Facetime.

[29:52]>> [Dr. Hartman]: Now, Cantos is a form of EPIC. And I can go into Cantos, so it's form of EPIC, and then I can read patient's notes. I can read their prescriptions. If a patient needs a refill, I can read that and hit a button and it allows me to approve it or not approve it or I can change it. So this has allowed me to work with EPIC. It's still somewhat limited. For example, I can prescribe a non-controlled drug, but I cannot do a controlled drug.

Time is a big challenge for someone with a disability

[30:31] So I'm going to move back to my bigger machine here and I'm going to just touch base in general about working with these tools. These different pieces of equipment are really wonderful and they opened a lot of doors to me. However, the major challenge that I work with, and I think most disabled work with, is time. It just takes me longer to accomplish the same thing other people do quickly. A simple example is for me to read a piece of article. If I read it in braille, I can do it about 90 words a minute. If I listen to it, it's a little faster, 180 words a minute, but I think the average person reads at close to 300 or more words a minute.

[Note: at this time we lost the in-person captions on Google Slides. We thought we had lost Zoom but only the captions on Google Slides were affected. Dr. Hartman continued his talk.]

[31:34] I'm sorry?

>> [inaudible].

>> So I don't know.

>> [inaudible].

>> We've lost connection? We're still okay.

[31:43] So time is one of the most challenging things that I and other blind people struggle with. What I have done in the office as I have a scribe that I support and she is able to read EPIC quickly, we're able to see patients quickly. And I've been able to see about 20 to 30 patients a day and move through their charts quickly, move through their message quickly, and just speeds up my accessibility a great deal.

How do you help someone with a disability?

[32:34] One of the things people come to me, whether is the idea, how do you help someone that has a disability? And I always like to tell the story about the two boy scouts that came home dirty and their uniforms were torn. And the mother said, what have you two been doing? They said, we were doing our deed for the day. And she said, well, what do you mean? Well, we helped a little old lady across the street. And, well, how did you get so dirty? Well, she didn't want to go.

And I think that so often the case. We think we know what people want, we think we know how they want help, but it's so important to step back and say, let's check with them to see how we can be at most help. And so I beg of you when you're not sure, just stop the individual and say, hey, how can we help or maybe you don't need help.

Everyone has a disability of some kind

[33:28] As we mentioned in the beginning, I think that in some way we all have a disability one form or another. Some of us are shy, some of us are overconfident. Some of us have trouble with attention deficit or learning disability. We all have a disability of one form or another.

Being blind can have its advantages

I remember when I was, I guess, in college. It was a summer camp I worked at. I had a very close friend who worked with me at the camp. And there were a lot of very attractive young ladies that work there as well. And this one day it was very very hot and we had an all camp swim. And my friend Wayne said to me, Dave, I very rarely feel sorry for you, but today I do. And I said, well, why is that? And he said, well, there's so many fine looking women in bikinis and you can't see them. So we all swam and it was a very crowded pool. And afterwards I pulled Wayne aside and I said, Wayne, I rarely feel sorry for you, but today I do. And he says, why is that? And I said, well, I've never bumped into so many fine looking women in all my life.

Those who are most disabled don't know what their disabilities are. Those who are least disabled turn their disabilities into advantages.

[34:41] So I argue that those of us who are [most] disabled are those who don't know what their disabilities are. Those of us who are [least] disabled are those of us who can turn our disability into our advantage.

As we strive to be the people we want to be in spite of low expectations, in spite of our various barriers, awkward situations, several things happen. First, society is forced to accept greater individual differences and thereby is enriched. Secondly, we ourselves grow from that struggle as we face the challenge of dealing with our disability, we grow.

The struggle only makes us stronger

[35:29] And there's a story about the chicken and the egg. The story is that as this chicken is growing up in the egg, it has to go through a hard process of fighting free of the egg shell to become independent and be on its own. But if you crack that shell and make it easier, the chicken doesn't do as well. In fact, they die during the first part of their life. That somehow that process of fighting free of the eggshell is a strengthening process that better prepares a chicken for the challenges of life.

And so I say as we struggle to be the people we want to be, in spite of low expectations, in spite of the various barriers, we ourselves grow. We become competent, more capable individuals who can fully achieve our potentials.

My doctor was my inspiration to go to medical school

[36:17] And I'm going to say one more statement to those of us in the medical field. I was taken care of by a doctor, Dr. Rob McDonald, from age 3-8. And during this time he struggled to save my sight. He did everything possible. And in the process, he showed me care and love and tenderness, gave me time. And in spite of the fact I never did gain my sight, this doctor gave me something much greater. In his care for me as an individual, in his sensitivity for me, he was able to give me inspiration. Inspiration to go to medical school. And so as we in the medical field and we as teachers, we're not going to cure everybody. We're not going to resolve each individual problems, but maybe we can share enough of ourselves to inspire them to make the best of their lives. Thank you so much. APPLAUSE

Questions and closing statements

[37:28]>> [Vianne]: Do you have any questions for Dr. Hartman?

>> [Audience member Danny Cordova]: How do you do, Dr. Hartman? My name is Danny Cordova. I'm a resident in pediatrics, but I was previously working with the Air Force [inaudible] General Medical Officer. That was how I paid for medical school. And I've had my own unique challenges as a result and your story is incredibly inspirational.

>> [Dr. Hartman]: Well, thank you.

>> [Danny]: I just wanted to thank you. And it's also inspirational because in pediatrics we're going to have all kinds of differently abled people. And I want to be able to encourage my patients and their parents to focus on all that they can do. And it's so reassuring to know that there are so many technologies and supportive platforms and a different mindset that we can use to really help them succeed and take care of themselves as much as they can.

>> [Dr. Hartman]: Thank you. I appreciate those thoughts. And I think the most important thing is to always ask them where they want to go and play a role as Mark said, how we can enable them to get there.

>> [Vianne]: OK, Well.

>> Yeah.

>> [Vianne]: Mark has a question, hold on.

>>[39:03] [Mark Nichols]: So with my background in assistive technology, this is a question I'd love to ask, is there a piece of technology, if you had carte blanche to design a piece of technology to help you further engage in your environment today, is there something that you would say “I wish I had a tool that did this?”

>> [Dr. Hartman]: Absolutely. I wish I had a tool that would enable me to use electronic medical record easily and quickly. That would just open up a lot of opportunities.

The talking traffic light at McClanahan

[39:39] Another thing that I just want to comment is, I've been practicing crossing streets and the curb cuts I know are wonderful but if you're blind, you can walk off a curb and not really fully be aware of it. And I know they have bumps but sometimes you think is just the bump in the sidewalk but at McClanahan and Jefferson, they have a talking light there. You can push the button. And I'm not sure I can imitate it fully, but it'll say "McClanahan walk sign is on." So you get a little Appalachian accent, it's great. I don't want to take up, we have one more speaker and I don't want to….

>> [Vianne]: Yes, we do. You shared a story about this McClanahan talking bit but also that now because of electric cars, you no longer can hear the cars coming down the street. So now you need that Texan or an Appalachian accent to cross the street.

>> [Dr. Hartman]: Absolutely. The quiet cars are a little scary to me. And again, if you see a blind person at the edge, you can always offer to help them across. And there are some blind people that would not be comfortable, they want across it themselves. If it's me, I'm glad to all the help I can get it. Thank you all so much.

>> [Vianne Greek]: Thank you Dr. Hartman.